This is a book I thought long and hard about highlighting. I expected great things and was overall disappointed. Unfortunately John Horgan is a reductionist materialist and despite the access he had to various spokespeople on mysticism, he remains thoroughly unconvinced. He is a science writer who holds the dogmatic party line through the entirety of the book. That said, I think some valuable perspective can be gleaned from the people Horgan talks to. It’s worth the read to get an overall feel for the modern history of the topic and hear from some of the players.

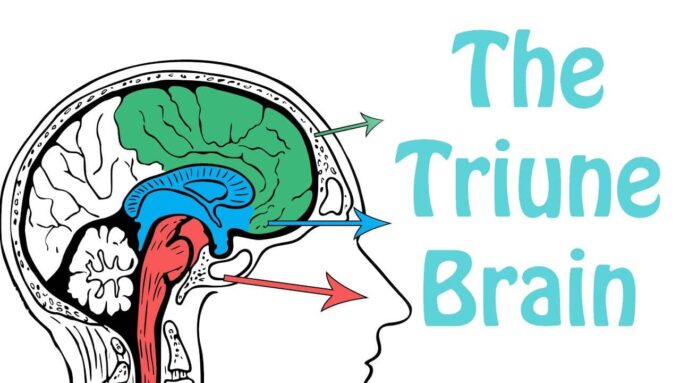

A t first glance the juxtaposition of Zen and brain function might seem odd, especially in an age during which scientific reductionism has produced striking advances. However, renewed interest in the mind-brain interface has created the need for synthesis rather than fractionation. Dr James Austin employs Zen meditation as a starting point for a wide-ranging discussion of the mechanisms of consciousness. Austin Zen and the brain. Creative, problem-solving. A glossary at the end helps to define useful terms. The next pages summarize aspects of 10 key conceptual issues.

Horgan begins with a definition of mysticism within the historical context. He interviews Huston Smith who discusses mysticism as a cross-cultural, cross-religious experience. Smith represents the notion of the perennial philosophy. The author’s search next takes him to a two day conference in Chicago where mysticism is treated as a literary phenomenon. These scholars know in great detail the texts left behind by Eckhart, St. Teresa of Avila, Shankara, etc. But sadly, none of them has any personal experience with anything remotely mystical. The journey continues with an interview of Ken Wilber dubbed ‘the weightlifting Bodhisattva’ by Horgan. Wilbur stands behind Smith adhering to the perennial philosophy but also embraces science as a way to explore and define mystical experience.

Important information is raised in the chapter called Can Neurotheology Save Us?. Horgan visits with Andrew Newberg, the doctor featured back in 2001 in Newsweek’s article, “God and the Brain: How We’re Wired for Spirituality.” Wouldn’t it be nice if brain scans could prove mystical states and help us to understand them? Unfortunately, a review of data collected on all sorts of meditation doesn’t support any nice clean conclusions according to Jensine Andreson, a theology professor at Boston University. And that in turn brings into question all the benefits touted for meditation. A review of the studies looking at meditation and its benefits Andreson believes, are poorly designed and won’t hold up to scrutiny. Of course, as it relates to mystical practice, mystics don’t meditate to lower their blood pressure but I would concede that a whole lot of Americans do increasingly view meditation as a health practice. Should they?

Zen Brain Lyrics

Continuing the scientific pursuit of mystical states, Horgan interviewed Michael Persinger of Laurentian University, Canada. Starting in the 1980s, Persinger began studying the brain’s response to electro-magnetic pulses to certain areas of the brain. 40% of Persinger’s test subjects experience a presence. The Canadian magazine Mclean’s called this device, “the God machine.” Persinger maintains that he has not addressed the God question with his work, rather his interest is in understanding the electrical pattern of the brain that leads to religious belief. But does the machine produce mystical experiences? No. Apparently, no one tested has reported the typical sensations of bliss, unity, or ineffability commonly reported by mystics. Scientific attempts to link temporal lobe excitation or epilepsy to mystical experience do not hold up either.

Horgan next turns to practitioner of Zen and neurologist, James Austin who penned the book, Zen and the Brain. Austin calls his approach perennial psychophysiology. Instead of gaining metaphysical insight, Austin thinks the mystic undergoes deep changes in personality. Someone who has had these experiences becomes more stable, more compassionate, and more selfless. As a specialist in brain disorders, Austin attempts to separate healthy mysticism from other illnesses. His approach relies on the idea that mystical experience releases excitotoxins which cause the loss of neurons. This in turn, allows us to get rid of those things that distort our view of reality. This is as scary as it is fascinating. For me, it makes mystical experience similar to brain damage. Can that really be? Jvc smart tv manual.

No book on mysticism would be complete without a foray into drug induced mystical experience. Horgan looks at the history of LSD, DMT, and ayahuasca. Download game booster terbaru apk. He visits Stanislov Grof, who is involved in the transpersonal psychology movement. Grof believes that we must move into a new paradigm where mind has primacy over matter (the book was published in 2003, not a unique idea now). There’s an interesting discussion of Rick Strassman’s work as outlined in DMT: The Spirit Molecule. The colorful Terrence McKenna makes an appearance in a later chapter where he advocates the use of psychedelics.

Photo by: vishwagna.com

The book is a nice romp through lots of questions with little in the way of conclusions. I often had the feeling that the author was totally out of his depth. Why did this topic appeal to him? He remained a science writer who attempted to fill pages. Most of them are interesting. I wonder what the book would have looked like with another author or even what the book would look like if updated.

Biography

Zen Brain Boosting Music

James Henry Austin was born in Cleveland, Ohio in 1925.

He attended Brown University, graduated from Harvard Medical School (1948), and did his medical internship at Boston City Hospital, where his first year of residency was in neurology. Austin's neurology teachers were Derek Denny Brown, Raymond Adams and Joseph Foley.

Austin's two years of naval reserve service in neurology were spent in Yokohama, Japan and in Oakland, California. In 1953, he began a neuropathology fellowship at Columbia University in New York, and then completed his neurological residency at the Neurological Institute of New York.

From 1955 to 1967, he held successive academic appointments in Neurology at the University of Oregon Medical School. In 1967, he was appointed Head of the Division of Neurology at the University of Colorado Medical School, then Chair of the Department from 1974 to 1983, and Emeritus Professor in 1992. During retirement, his appointments have included Affiliate Professor of Philosophy at the University of Idaho and Courtesy Professor of Neurology at the University of Florida College of Medicine.

His earlier research was in clinical neurology, neuropathology, neurochemistry, and neuropharmacology. His first sabbatical was spent at the All-India Institute of Medical Sciences in New Delhi. During the second sabbatical at Kyoto University Medical School in 1974, he began Zen meditative training with Kobori-Roshi, an English-speaking Rinzai Zen master. As a Zen practitioner, he has since become keenly interested in the ways that neuroscience research can help clarify the meditative transformations of consciousness.

Austin's interest in the psychology of the creative process led him to write Chase, Chance, and Creativity, published first by Columbia University Press in 1978, and then revised in 2003 as an MIT Press edition.

His interest in Zen Buddhism has led to four MIT Press books. Zen and the Brain (1998), currently in its 7th printing, was followed by Zen Brain Reflections (2006), Selfless Insight (2009), and Meditating Selflessly (2011), Zen Brain Horizons (2014), Living Zen Remindfully (2016).

His marriage to Judith St. Clair has been blessed with three children ( Scott W. Austin, Lynn S. Manning and James W. Austin) and three grandchildren (Nicholas Manning, Katharine Manning and Elizabeth Manning). His wife passed away from Alzheimer's disease in 2004. Austin lives in Columbia, Missouri.